There are some people on the sidewalk you don’t even notice, no matter which direction they are going. Then there are those who are stopped (maybe window shopping, out of breath, sprained ankle, lost, bending over tying a shoe) and you run into or over them, giving you the opportunity to account to them and ask for forgiveness, depending upon how hard you rammed them. As for those going in your direction, some are not moving at the pace you want them to, and are in your way, annoying you; others are going too fast, bumping you from behind as they attempt to pass you, and annoying you.

As for those going the opposite direction, walking toward you on the sidewalk, some brush against you with no effect; others slightly jostle you and, though not really impeding your progress toward your destination, annoy you; some people seem to block your path as the two of you “dance” back and forth in temporary frustration, each trying to occupy the same space; others might run into you hard enough to knock you off course momentarily—some apologize and some don’t; and, last, there are some who really injure you as they run right over you in their mad dash to wherever, or from whatever—some apologize and some never will.

And then you get to work and have to deal with the boss!

I recently read Hurt People Hurt People, by Sandra D. Wilson, who also wrote Released From Shame. I found it very profound and helpful, and will share some things from it with you shortly. But to pursue the sidewalk analogy a bit further in light of the book’s title, what happens when someone going in the opposite direction whacks you? You most likely look around at him as he goes by you and draws farther away from you. It seems that the more someone hurts you, the longer you keep looking back at him as you walk. How many people do you then ram into and injure, let alone the number of utility poles, fire hydrants, and open manholes that injure you? The point is that when your past becomes your present, it wrecks both your present and your future—and those of others also.

If you are injured to the degree that you cannot walk normally, or at all, you no doubt look for other pedestrians on the road of life who could help you, and very likely grab on to the first person you can. But that, of course, requires some degree of trust, which, considering the general state of the population, is risky, to say the least. And if the pattern in your life is that when you expressed need or vulnerability, you were rejected, abused, and belittled, your capacity to trust is severely limited, and you must somehow work through great fear in order to reach out to others.

One thing that will definitely hinder us from making the progress necessary for enjoying intimate relationships is a “victim mentality.” Unfortunately, that attitude comes naturally to us. Why? Because every human being is a victim—of Adam’s sin! And not only in the sense that we inherited from him a sin nature that loves to wallow in self-pity, but also because the sin nature in others causes them to harm us. As a result, we legitimately hurt, and usually erect appropriate defense mechanisms to wall off ourselves from what hurt us, especially as children when we experience trauma that overwhelms our capacity to understand and process it.

Too often we carry these necessary and temporarily effective defense mechanisms, such as detachment, anger, trying to control others—or please them (perfectionism), into our adult relationships, where they fail us miserably. So that our past does not become our present, we must properly process its pain. How do we do that? By first recognizing how bad it really was and allowing ourselves to feel the pain, and then by accounting for any part we played in it (which may have been none), grieving it deeply, truly forgiving those who wronged us, and letting it go, once and for all. In Hurt People Hurt People, Sandra Wilson writes:

“I doubt that we can put our pasts behind us when we’ve never put them before us. Yet many of us stall on the starting line of change because we fear what we’d lose if we did. We must count the cost of change with ruthless realism.

If we do not, these unresolved past issues with parents or others who injured us generate the same feelings and make the same impact on our present relationships. That is because I can experience you in the present only to the degree that other internal issues do not get in my way. When they do, I am not really with you, and thus I do not really know you. Rather, I am with the person in my head from my past, of whom you remind me in some way. It’s sort of like having a bent frame on your car that keeps you from driving straight even though you try.”

THE GOOD NEWS IS that JESUS, who could have adopted the ultimate victim mentality because he was both the most innocent and most abused human ever, chose instead to show us how to deal with injustice by recognizing its source and drawing upon God’s provision to forgive and love those who sinned against him. AND he has equipped us to think and act likewise. OK, how do we get there? Not by ourselves, that’s for sure.

First, we recognize that we cannot do it alone. Sorry, but people who need people are not the luckiest people in the world. Everybody needs people, for heaven’s sake. Even children know that, at least those who have watched the Veggie tales episode of “Dave and the Giant Pickle,” because, as one of the French pea Philistines says when laying out the terms of surrender if the Giant Pickle kills Dave: “And you have to scratch that little place right in the middle of our back that is impossible to reach, no matter how hard we try.” I need people to reach those places in my life that I can’t reach on my own.

No, it is people who recognize that they need people who are “lucky.” At least they have a clue. Hey, back to the sidewalk. If you have been knocked down, even flattened, and you still want to get where you were going, you need people to help re-orient you, guide you, and maybe even carry you for a while. We especially need people to help us do what 2 Corinthians 13:5a exhorts us to do: “Examine yourselves to see whether you are in the faith….” I heard recently that “the unexamined life is not worth living,” and that is probably not far from the truth. The problem is that our sin nature leaves us all with “blind spots,” which are virtually impossible for us to examine alone.

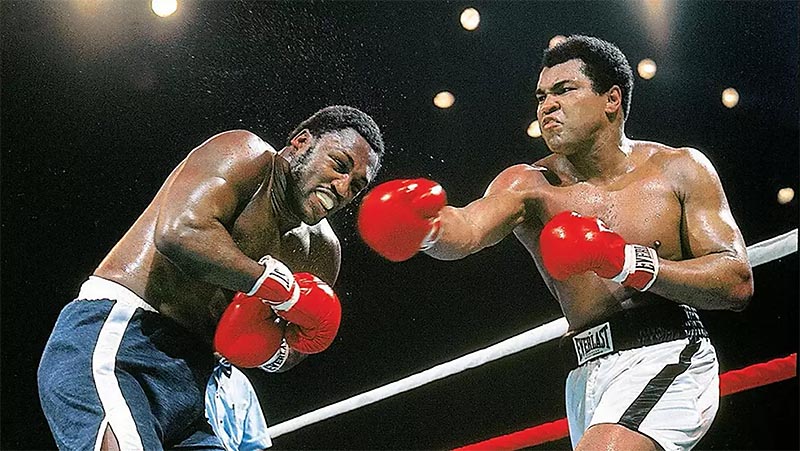

Recently, I told someone: “I’m in your corner” (Not to be confused with: “I’m your coroner”). Later I thought about what that really means. You probably know that it is an expression relating to the sport of boxing. Every three minutes the bell rings, and each combatant retreats to his corner of the ring where he fights other people. No. Where he looks around for a stool, some water, a towel, medicine for his cuts, and then gives himself a pep talk? No, there are people there to do that for him—people who care about him and can see what he needs more clearly than he can. Sometimes they are forcefully “in his face,” like maybe: “Look, daggone it, keep your left up! He’s hammering you with that right hook!” And, in the spiritual war zone known as “life,” each Christian needs his “seconds”—and thirds and fourths!

Unfortunately, that does not mean that we are exempt from our solitary “wilderness walk.” No, it is only in conjunction with our doing the internally excruciating work of dying to sin (self) that the help of others is effective. It is “excruciating” because the Latin word crux means “cross,” and our death to sin is akin to what Jesus experienced on the Cross for us. It was his crucifixion whereby the term “excruciating” was coined. That tells us that the only way to gain is through great pain. The only way to resurrection life is through death.

In Chapter Three (“Removing the Veil”) of his landmark work, The Pursuit of God, A. W. Tozer writes:

“The veil is not a beautiful thing and it is not a thing that we commonly care to talk about. But I am addressing those thirsting souls who are determined to follow God, those who will not turn back when the way leads temporarily to the blackened hills. The urge of God within them will assure their continuing pursuit. They will face the facts, however unpleasant, and endure the cross for the joy set before them. So I am bold to name the threads out of which the inner veil is woven.

It is woven of the fine threads of the self-life, the hyphenated sins of the human spirit. They are not something we do, they are something we are, and therein lies their subtlety. To be specific, the self-sins are self-righteousness, self-pity, self-confidence, self-sufficiency, self-admiration, self-love, and a host of others like them. They dwell too deep within us and are too much a part of our natures to come to our attention until the light of God is focused on them.

Self is the opaque veil that hides the face of God from us. It can be removed only in spiritual experience, never by mere instruction. We may as well try to instruct leprosy out of our system. There must be a work of God in destruction before we are free. We must invite the cross to do its deadly work within us. We must bring our self-sins to the Cross for judgment. We must prepare ourselves for an ordeal of suffering in some small measure like that through which our Savior passed when he suffered.

Let us remember that when we talk of rending the veil we are speaking in a figure, and the thought of it is poetical, almost pleasant, but in actuality there is nothing pleasant about it. In human experience, that veil is made of living spiritual tissue, it is composed of the sentient, quivering stuff of which our whole beings consist, and to touch it is to touch us where we feel pain. To tear it away is to injure us, to hurt us, and make us bleed. To say otherwise is to make the Cross no cross and death no death at all. It is never fun to die. To rip through the dear and tender stuff of which life is made can never be anything but deeply painful. Yet that is what the Cross did to Jesus, and it is what the Cross would do to every man to set him free.

Insist that the work be done in very truth and it will be done. The Cross is tough and deadly, but it is effective. It does not keep its victim hanging there forever. There comes a moment when its work is finished and the suffering victim dies. After that is resurrection glory and power, and the pain is forgotten for joy. The veil is taken away, and we have entered in actual spiritual experience into the presence of the living God.”

Speaking of pain, Rick Reilly, whose writing I really enjoy, wrote a column in the May 16 issue of Sports Illustrated. It is titled “Extreme Measures.” Good Lord! Not when I first read the article a couple days ago, but only just this very second as I wrote the last sentence did I think of Jesus’ admonition: If your right hand offends you, cut it off! Where is my “second” to throw some cold water in my face and wake me up?!

Sometime about the first of May, Aron Ralston’s right hand, up to his lower forearm, had been “offending” him for three days. That’s how long it had been pinned beneath an 800 pound boulder that had shifted onto it while he was climbing alone in a remote section of Utah. Reilly attended the press conference where the 27 year old Ralston told about his adventure, and wrote in his column: “On the third day, out of food and water and ideas, he stared at his cheap, multiuse tool, the kind you get free with a $15 flashlight, and realized what he had to do. He used a pair of cycling shorts as a tourniquet, picked up the knife, took a deep breath, and began sawing into his own skin.”

It took Ralston two days of cutting on himself to get down to where his wrist bones were the only things not severed, and there he had to stop because the knife would not cut through them. The idea came to him to break the bones in his already flayed arm, which took him a whole morning as he used torque and what strength he had left. Then he stretched his body away from his hand in order to separate the broken ends of the bones, and used the knife to finish the job. That took an hour, after which he crawled through a narrow, winding stretch of canyon, rappelled 60 feet down a cliff and hiked six miles until he met two hikers.

As I read the column, by far the most profound part for me was what Ralston said about the mindset he adopted in order to cut off his own arm. “All the desires, joys, and euphorias of a future life came rushing into me, and maybe that is how I handled the pain. I was so happy to be taking action.”

Does that remind you of someone else who had to endure far more pain and suffering than Ralston, and not because of his own error? The Lord Jesus, “…who for the joy set before him, endured the cross…” And what about you and me as we stand on “the starting line of change,” apprehensively anticipating the pain and the tears that will be required to enter into the truth about our lives and go through the process of change we need? Can we not hold on to the joy of resurrection life guaranteed to those who choose the death of self? Can we not take “extreme” action to enter into the pain, expecting God’s promises to come true?

Basically, a person registers trauma on the right side of his brain, and when it is properly processed, that is, when we put words to it and get it out into the light, we move it to the left side of the brain, making it linear in our experience. It then can fade into a scar, significant in the memory thereof but not debilitating to our lives. If we do not process it in a healthy way, it stays on the right side of the brain and, as it were, never knows what day it is. That is to say, it remains in the present, and we make poor choices based upon our mentally and emotionally re-experiencing the trauma.

Wilson writes: “God is calling us out of dark, dank caves of denial into the honest risk of truth’s light.” And then this classic statement: “When we hide from painful truths, we deprive ourselves of discovering that Jesus, the Great Physician, is as able to heal our unseen wounds as He is to forgive our sins.” Think about that one. It is captivity to relate to our past in any way other than to allow God to transform us. In fact, it borders on idolatry not to recognize His power to create life out of death and trust Him to do so.

In the last chapter of her book, Wilson states that our hope is certainly not for pain-free living. Even if those who badly hurt us repented and asked for our forgiveness, our lives have still suffered the ill effects of those wounds. She says that our misguided attempts at self-supervised healing have only added to our hurt, and hurt others we love. So our hope is not for a life that was never wounded, nor for the erasure of suffering. She then waxes eloquent about what she calls our “stewardship of weakness and suffering,” saying that God wants us to bring Him our weaknesses so He can bear them for us. When we need Him most, He comes alongside to help us, and “our fear of personal weakness evaporates like morning fog in the dazzling light of His strength and grace.”

Citing 2 Corinthians 1:3 and 4, Wilson says that God is both our Creator and our Comforter, and that “the good news is that we really will experience His supernatural comfort when we suffer. The bad news is that we really will experience God’s supernatural comfort when we suffer. Said differently, God’s comfort is the greatest show on earth, but the price of the ticket may kill you!” We are to be “conduits” of His comfort by entering into the necessary pain and suffering, taking in all of His comfort we need, and sharing the overflow with others who are also suffering.

Wilson also speaks of the “stewardship of our scars,” and writes:

“To all of us, Jesus identifies himself by his scars. On a corpse, scars tell us how the person died. But Jesus comes to us alive; his scars speak of triumph over betrayal, victory over evil, life out of death, hope beyond despair…Some of our scars speak loudly, others softly, but each has a story to tell. Good stewardship of our scars involves letting them tell his story. Letting our scars—the signs of our woundings—tell God’s story is what Scripture calls a “sacrifice of praise.”

Of all hopes, this is the greatest: the promise of God’s everlasting love. He plasters that promise from one end of His Word to the other. Jesus was the consummate container, the incandescent explainer of God’s everlasting love. Just think of how Christ’s ministry matched our misery. We come bruised, broken, and bound. Jesus comes healing, mending, and releasing. At this perfect fit of need and provision, we see the union of God’s scars and His everlasting love.

This very moment, God offers each of us His multi-faceted, ever-living hope to comfort us, to encourage us, and to undergird each step of our journey from hurting to healing. He gives us hope for stewardship of weakness and suffering that brings blessings to us and to others while bringing glory to God; hope that as we embrace the reality of choice, change, and transformation, our scars will sing the praises of our living and loving Savior; hope that sees in the splintered fragments of our broken lives the reflection of his empty tomb.”

So let us keep moving along together on the sidewalk of life, walking in the light, examining ourselves, being in one another’s corner, taking whatever extreme measures are necessary to enter into whatever pain we must face for the joy set before us of becoming like our glorious Lord, receiving the healing he longs to give us, letting our scars tell the story of his deliverance, and pushing the envelope, on the edge of faith.